Using Rubrics to Inform and Support Learning Outcomes

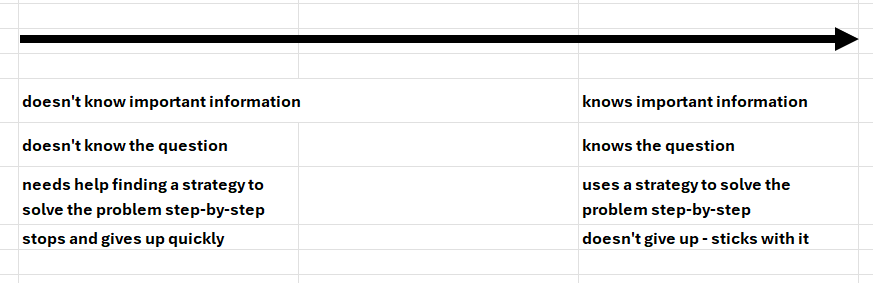

Last week, I discussed how to modify and use a rubric as a feedback tool for students to reflect on their growth and visually see their progress over time. Below is a rubric I created for a student to help them see their progress solving word problems. I used Peter Liljedahl’s suggestions of an arrow along the top (no headers), and three columns. The first column notes the lack of skill, the last column lists the specific skills needed to solve word problems, and the middle column is empty. My student will be able to mark where they are on the continuum, reinforcing the idea that learning is acquired over time.

In this blog, I will review Peter Liljedahl’s work from his book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics on developing more informative rubrics that can be used for grading and providing meaningful feedback to students and the teacher on students’ growth over time.

Liljedahl states that information on students’ progress is shared between the teacher and the students either through a graded assessment, rubrics, exit tickets, teacher notes or other means. However, he also states that this information is not always useful for students because students only see how they performed on that specific skill or content that was evaluated. They do not see the feedback in the larger context of the unit of study. So they know what they can do, but they don’t know what they cannot do yet, (pp. 232, 233).

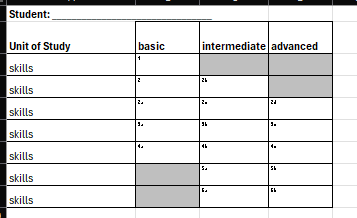

In response, Liljedahl worked with teachers to create a rubric that showed students what they can do and what they cannot do yet, or where they are going. This rubric includes skill specific headers of basic, intermediate and advanced. The specific skills and content areas are listed on the left (see diagram below), and if a skill can only be categorized as basic, then the boxes for the other two columns are blocked out. The same is true for a skill that is only in the advanced range, the basic and intermediate boxes are blocked out. In addition, to help students see the progression in learning, specific problems or parts of problems can be marked for each box in the rubric. A rubric designed in this way will not only clarify expectations for students, but also clarify the learning path, (p.236).

The other benefit of a rubric structured in this manner, is that it simplifies grading. Too often how students perform on exit tickets, rubrics and classwork can be very different than how they perform on assessments. For some reason, the knowledge does not always transfer. Liljedahl found that by adding a simple key to score the rubric was enough to provide students with meaningful information on what they answered correctly, what they could do with help, where they made silly mistakes but understood the concept, and what they did not know either through not trying or just not being able to solve, (pp.237-240). Below is a sample rubric with a key that reflects these categories. In this sample, I eliminated the collaborative group category that Liljedahl uses because I work one-on-one with students.

But how did Liljedahl use this rubric to inform the grading practice? Liljedah assigned points to each column, two points for basic, three points for intermediate and four points for advanced. If a particular skill in the rubric only had a basic column, then it was only worth two points, but if it extended to the advanced column, then it was worth four points. If you look at the examples below, there is a blank rubric I made and an example from Liljedahl’s book. Students’ scores for a particular skill depends upon the where they are able to show that they attained the skill with two consecutive checkmarks, (pp. 262,263). For example, in Liljedahl’s sample rubric, this student showed attainment for solving contextual problems involving fractions at an intermediate level (two consecutive check marks), so they earned three points out of four because the skill extends to the advanced column. The grade for this student is then determined by finding the percentage of the students points, (p. 264). This rubric structure makes students’ learning very visual and shifts the focus from earning points to learning outcomes. As a result, Liljedahl saw an increase in students’ interest in attaining new knowledge than they were in acquiring points, which is the traditional way to determine grades, (p. 267).

As a teacher with a Special Education background, this type of informative rubric would not only inform my students on their progress towards their goals and learning specific skills, but it would also provide data for progress reports, parent-teacher conferences, and collaboration with other teachers. As a tutor, this rubric provides both my students and their parents the information they need to see how students are progressing on their tutoring goals.

If you have a comment or question, please email me at lindapatrellkim@gmail.com or use the button below.