The How, The When, The Where of Assigning Thinking Tasks

This week let’s talk about how we, as teachers, answer questions and how we assign thinking problems to students.

In his book, Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Peter Liljedahl shares his research on the different types of questions that students ask. The first being proximity questions, which are the questions that students ask when the teacher is nearby to show that they are working. The second type of question is what Liljedahl calls a stop-thinking question. This type of question is used to elicit information from the teacher so students can stop thinking. The third type of question students ask is what Liljedahl calls a keep-thinking question. This type of question is used to gather more information to clarify, extend thinking and engage more with the problem. In his research, Liljedahl found that to get students thinking, teachers needed to ignore proximity questions and stop-thinking questions, or answer them with a reflective question that elicits thinking. Furthermore, when students were aware that the teacher would not be answering these types of questions and would instead provide reflective questions, their engagement and persistence increased (pp.84-90).

Liljedahl also researched the manner in which teachers gave a task to the class – how it was given, when it was given and where it was given to determine how these factors influence student engagement and thinking. Liljedahl observed that this included giving work from a textbook, workbook or worksheet and a written or projected problem on the board. Next, Liljedahl examined if the task or problem was given at the beginning, middle or end of the lesson, and, finally, he examined where the students were when the task was given, seated at their desk or standing. Liljedahl’s findings may surprise you (pp. 101-105).

When determining how to give a thinking task to students, Liljedahl found that students displayed more engaged thinking behaviors when problems were projected or written on the board, or even given as a handout compared to working from a textbook or workbook (p.100). When examining when to give a task, Liljedahl discovered that tasks given at the middle or end of a lesson resulted in lower engagement and thinking behaviors compared to tasks given at the beginning of a lesson. Liljedahl also discovered that the longer teacher talked, the increased likelihood that the teacher would preteach the task either by providing parallel examples or ways to represent and organize the task. In addition, Liljedahl notes that the initial instruction for the thinking task needs to stay within the first five minutes of the lesson. Anything over five minutes results in decreased student attention and engagement and increased possibility of the teacher undermining the thinking task by preteaching (p. 101-102). In regards to where the problem is given, Liljedahl shared that students sitting at their desks were more likely to disengage during instruction for the task than students who were standing. Liljedahl collected data on cell phone use with high school students and found that nearly 50% of students who were seated were using their cell phones at least once during that five minute period of instruction compared to students who were standing, which was less than 10% (p. 104). Finally, Liljedahl states that even if teachers optimize the how, the when and the where, it is the discourse, the conversation between the teacher and students during the instructions about the problem that is critical. That discourse provides context for the students to organize their thoughts and ideas. Without this conversation, students may misinterpret the problem or just not understand the problem (pp. 105-106).

As a teacher, I posted four problems on the board for students to solve independently as they transitioned into the classroom. Those four problems were always a review of something recently taught or content taught earlier in the year. Students sat at tables and worked on the problems in their journals or on a handout I gave them. I walked the room during this five minute period to see how students were doing, answering questions and collecting informal data on my students’ needs and strengths.

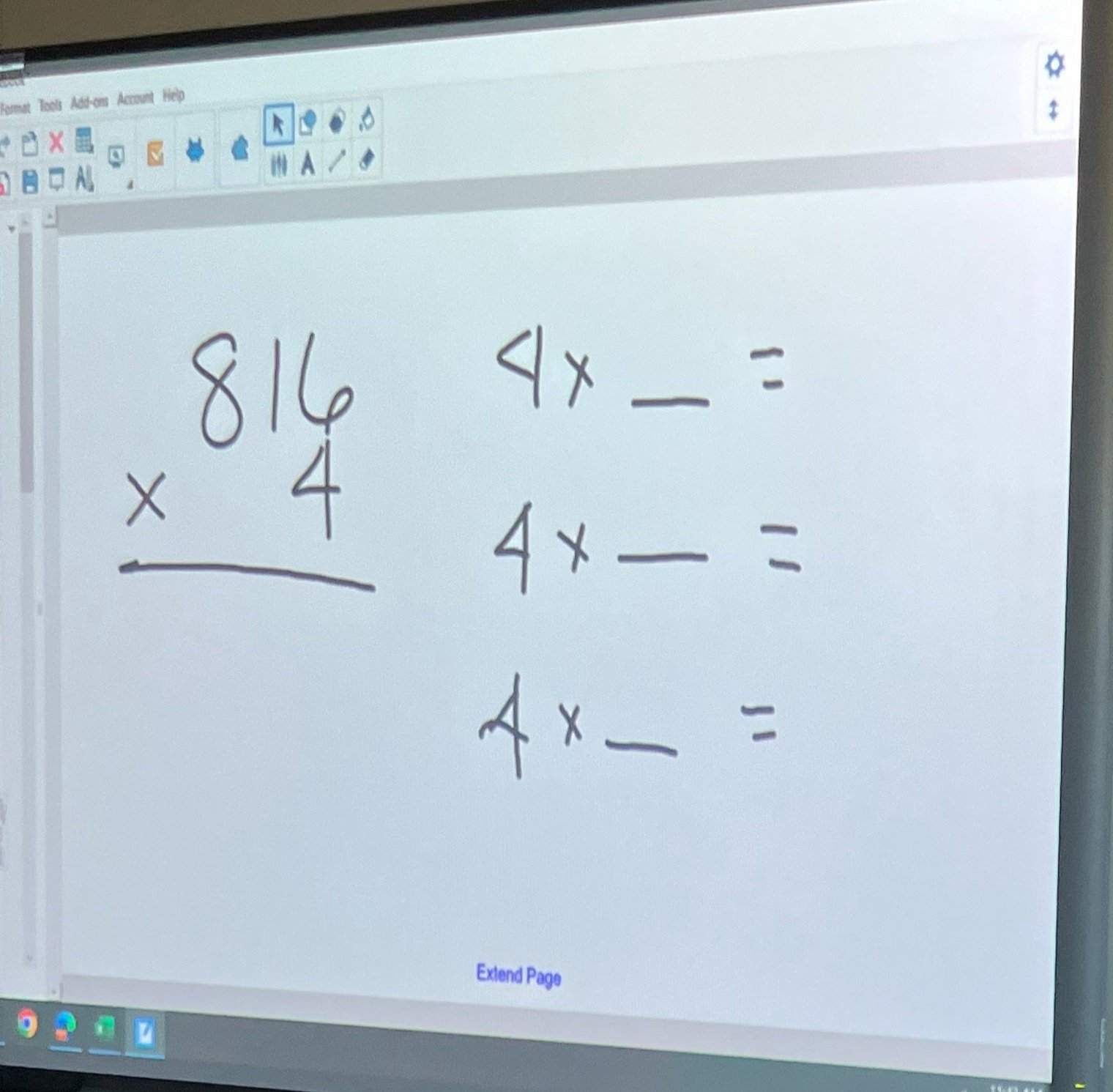

After reading Liljedahl’s research and reflecting on this practice, I recognize that I can improve this practice to increase engagement and get my students thinking. To begin with, I would keep the transitional work on the board as students entered the classroom, but I would adjust the work to reflect two review problems, a computation problem and an application problem that extends students’ thinking. I would allow for flexible seating or standing (accommodation for some students), but I would assign students to random groups as they walk in the room. (Popsicle sticks are great for this.) While students are entering the classroom, the computation problem allows time for all students to settle in and get to work. Once everyone was settled, then I could review the application problem with the students, make notes on the board based on the conversation, and then release them to finish the problem. I would still walk the classroom to check in with students and observe their strengths and needs. In addition, I would wrap up this time with students sharing their work with each other so they have a chance to compare different methods as well as examine their mistakes.

If you have questions or comments, you can send me an email to lindapatrellkim@gmail.com or use the button below.